Without any doubt the most exciting thing about the peregrine falcon is the way it catches it's prey. The falcon feeds on fresh caught prey like small birds,or small mamals. He is a raptor, or bird of prey. No picking little seeds here but killing to survive.

In order to catch a prey, a peregrine needs intelligence. He has to be able to anticipate immediately in a split second on the escaping behaviour of it's prey. No hunt is the same. It will not come as a surprise to know that the peregrine is one of the most intelligent avians. Together with raven it is on top of the Bird IQ list.

Every raptor has a special technique to catch a prey. Just think of the lion, or a shark, a cheetah. The peregrine falcon is beyond compare, but if we have too, we'd best compare it to the cheetah. The peregrine falcon however is faster than the cheetah. In a stoop the peregrine can reach speeds over 350 km/hour. And that's dazzling.

Evolution has streamlined the body of the peregrine falcon, gave it highspeed wings in order to reach the perfect form of a falling waterdroplet. Even the wings have this special airfoilform.

Without making it to technical with aerodynamics, somethings can be said about the stoop techique. And the very unique adaptions to the peregrine body.

Everybody knows how difficult it gets to breath when you're walking in a heavy storm. You have to turn your head to be able to breath. The peregrine falcon does not walk in the storm, it dive-bombs at 350 k/hour. Breathing would be absolutely impossible without special adaptions. The air pressure from a 200 mph (320 km/h) dive could possibly damage it's lungs, but small bony tubercles in a falcon's nostrils guide the shock waves of the air entering the nostrils (compare intake ramps and inlet cones of jet engines), enabling the bird to breathe more easily while diving by reducing the change in air pressure. To protect their eyes, the falcons use their nictitating membranes (third eyelids) to spread tears and clear debris from their eyes while maintaining vision.

The peregrine falcon searches for prey either from a high perch or from the air. Once prey is spotted, it begins its stoop, folding back the tail and wings, with feet tucked.It tumbles and dive-bomds downward. But not in a straight line.

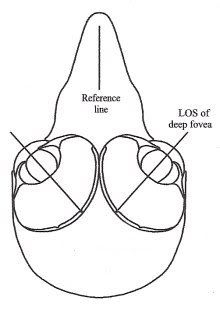

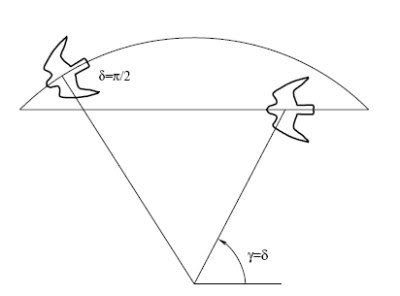

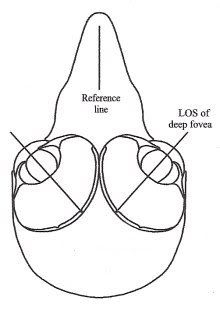

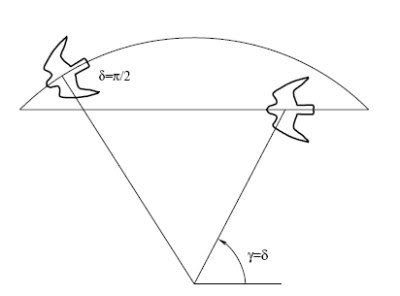

It approaches it's prey in a curved flight path because of it's sideway vision.When diving at prey straight ahead from great distances at high speeds, a peregrine has a conflict between vision and aerodynamics: it must turn its head approximately 40 ° to

one side to see the prey with maximum visual acuity at the deep fovea of one eye, but the head in this position increases aerodynamic drag and slows the falcon down. The falcon could resolve this conflict by holding its head straight and flying along a logarithmic spiral path that keeps the line of sight of the deep fovea pointed sideways at the prey. Wild peregrines, observed with binoculars, telescopes and a

tracking device, did approach prey from distances of up to 1500 m by holding their heads straight and flying along curved paths that resembled the logarithmic spiral.

Prey is struck and captured in mid-air; the Peregrine Falcon strikes its prey with a clenched foot,kind of a fist, stunning or killing it, then turns to catch it in mid-air. The Peregrine will drop it to the ground and eat it there if it is too heavy to carry. Prey is plucked before consumption. The juveniles have to learn all these things: the stoop, how to knock a prey dead, how to kill, and how to pluck. In the months after they fledge they will learn this from their parents, It are hard lessons. We have been able to watch how parents leave prey in the nestbox to force them to try in order to get food. As soon as one of the juveniles has left the nestbox the other ones have to as well. The parents will feed outside. So if they want food they have to step out as well. It seems tough and it is. Next stage is getting them all up in the air. When the first is in teh air, the feeding takes place far from teh nestsite. It's obvious the left-behinds have to fly in order to get food.

When all are airborn, lessons start. With food once more. One of the parents flies in with food in the talons. One of the juvi's will be the first one to take it over the prey and this is his or hers. So it is constantly a competition. The winner takes it all.

Copyright Froona ©

Click the pictures to enlarge

Click the pictures to enlarge